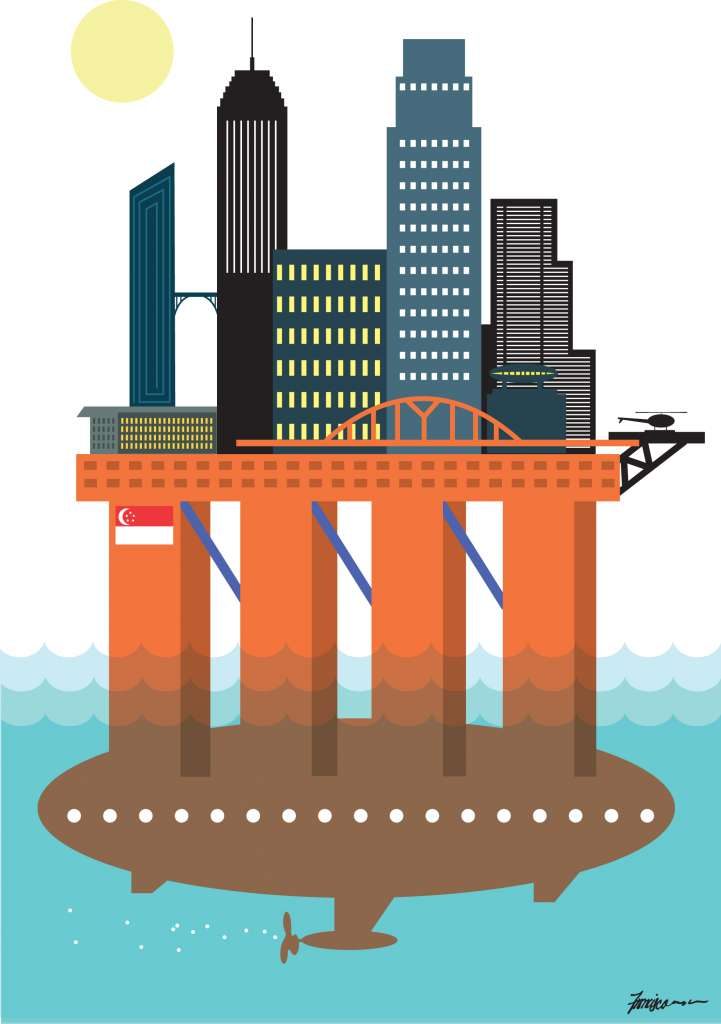

Vision SG100: Floating cities in the sea

Lim Soon Heng For The Straits TimesPUBLISHEDOCT 7, 2015, 5:00 AM SGT

With its expertise in marine engineering, Singapore can build floating cities in the sea to house industry and even residences

From my apartment, 20 storeys above the sea, I see Changi Airport straight ahead 8km to the north.

Where the old container port used to be, Keppel Maritime City is silhouetted against a backdrop of a scarlet sunset 16km to the west. I am enjoying my favourite drink, my feet tapping to the music of Ravel’s Bolero.

SG100, in 2065, when the country is 100 years old, can be a City in the Sea, vibrant, clean, noise-free and ecologically sensitive to the environment.

REAL ESTATE ON A DIFFERENT PLANE

Singapore architects and engineers designed this building. A Singapore-owned shipyard based in Bintan Island built it. The mechanical and electrical systems – imported from Europe, the United States and Japan – were all shipped directly to and installed in the shipyard in Bintan.

When this building arrived here, fully outfitted, two years ago, there were only three apartment blocks in this floating condominium off the shore of Bedok. Since then, two other blocks, one built in Malaysia, the other in the Philippines, have been added to the community.

Each block of apartments has a licence granted by the Maritime and Port Authority (MPA) to moor here for 30 years.

That 30-year lease may be extended on condition that MPA reserves the right to relocate it anywhere in the eastern mooring bloc if required.

The developer may build another building (subject to the Building and Construction Authority’s approval) to replace an old one. The residents’ migration from the old to the new building takes two weeks. In the past, the process of upgrading an existing building involved vacating the premises for a year or two.

Now, after rehousing his tenants, the owner tows away his old building to another country. With some facelifting work, he fetches a better rental from tenants in a less- demanding environment. It is a rewarding and an environmentally friendly solution. The old building isn’t demolished, but gets a new lease of life and continued rental gains for the owner.

The allocation of mooring rights comes under the purview of the Coordinating Minister of Infrastructure through the ministries of National Development and Transport via their respective agencies, the Floating Development Authority (FDA) and the MPA.

While there are no physical highways in the sea, corridors for navigation of watercraft have to be preserved in the planning of the sea space. Even though floating buildings are movable, meticulous planning is important as our territorial water is only about 800 sq km, not much larger than the land surface.

The Ministry of Defence also takes an interest to ensure that its floating naval base has quick access to the mainland for logistical reasons. The airspace is under surveillance by the ministry because short-range flying transport equipment for conveyance of passengers and goods is used rather extensively these days over land and sea all over the world.

The shorter mooring lease of 30 years may at first glance compare unfavourably with the 99-year lease on land. But this is not so.

The former is a mooring right lease for a movable asset in the sea, while the latter is an immovable asset on a plot of land.

The owner retains title to the property (in legal-speak, a chattel) for the life of the asset or until it is transferred. The 30-year lease enables the FDA to plan on a shorter cycle and to adapt and respond to fast-changing technologies. Floating structures in the early days were mostly less than six storeys. With a growing population, FDA envisions apartments on gravity-based structures that are 100 storeys high.

Developers of floating properties take ownership of power, water and waste disposal in the same way that a cruise ship is responsible for its provision of these services to the passengers.

With more than 2m of precipitation annually, we need only desalinate about 50 litres of water per day per resident. Desalination is carried out with the heat from the incineration of trash from the households of the condominium, supplemented by the renewable energy of the sea.

All exhaust gas is treated to comply with MPA rules and Marpol (the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships).

About 50 per cent of the electricity is derived from wind, waves, current and solar energy. We have two floating power plants powered by LNG from a central floating regasification unit. As the plants and storage unit are all mounted on barges, they may be towed away in case of fire in the vicinity or for servicing at a local shipyard.

VISITING THE FLOATING CITY

We had a visitor the other day, very curious about our lifestyle. We took him out for a ride in our amphibious helicopter (we do not own a car).

He was surprised when the chopper took off after we keyed in the destination with our cellphone. “Who is driving this thing?” my friend asked, somewhat alarmed.

“Oh, a computer in the LTA office,” I replied.

After the helicopter landed us on the roof of our cruiseship-lookalike shopping mall and entertainment centre, it took off and flew back to base. We will summon it back to pick us up from the same spot when we are done. “Man, isn’t it great you need not have to find a place to park? Like back to the old days with a chauffeur-driven car. But what happens if there is a mechanical failure?”

“No problem, Mike. The onboard computer sends a signal to LTA computer and asks for permission to abort flight and to land at the nearest safe place in the sea to await the recovery team.”

The next day I took him for a spin around St John’s Island and Sentosa in our little speedboat. “Don’t tell me this thing is driverless too,” he said, as we approached the pier.

“Of course. No one is allowed to drive a boat in public areas. I just key in my destination with my cellphone and then sit back until we reach our destination. We send it back with a stroke on this touchpad.”

Mike was clearly impressed. “You know I spend about three hours a week parking my car and walking from my carpark to my underground office, not to mention the parking fees and the traffic jams. In my lifetime, I reckon I spend about 8,000 hours parking and un-parking my car. That, my friend, is almost a year of my life!”

It was still early after our trip, so we decided to stop by my little floating garden close to my apartment. “I love these – tomatoes, chillies, spinach, and lady’s fingers growing in sea water! Yes, I know scientists have succeeded in modifying the genes of plants , so they become salt-water resistant, but this is the first time I am seeing it with my own eyes!”

We barbecued the crab that had been caught in the trap I set a few days ago. After a few cans of beer, we had a short snooze as we were driven back by a virtual driver in cyberspace.

“Tell me, all these floating structures, what do they mean to those still living on the mainland?”

“A lot. All those industrial plants, shipyards, incinerators, oil and gas storage tanks, metal fabrication shops in Jurong and Tuas are gone.

“Part of the 4,000ha of land freed by their move are now populated by research and development organisations seeking to harness renewable energies of the ocean. They develop prototypes and produce all manner of devices to generate power from currents and waves and, of course, wind turbines. Some are developing processes to produce food and biofuels from kelp.”

“But you do not have a market?” he interjected.

“Of course, we have. The world is our market. Our devices, like our offshore oil rigs in days of yore, are used all over the world.”

“Where have they gone, these facilities which were there?” he asked.

I replied: “They are now based on very large floating platforms in the sea south of Tuas. This is an excellent solution. The tens of thousands of foreign workers working in the shipyards now live in floating dormitories near their place of work, removing social and space pressure on mainland Singapore.

“The risk of fire and toxic gases from incinerators and our nuclear power plants affecting residents is now more remote as they can be moved out to the open sea when an accident occurs.”

A REALISABLE VISION

One may well ask if the vision above is merely science fiction. Are floating cities, parks and recreation centres, industrial estates and ports and airports the products of an overactive imagination?

In the past four decades, Singapore shipyards have been delivering offshore production and exploration facilities and floating accommodation, which are employed in harsh oceans in the Northern and Southern hemispheres.

Research and development have been carried out and treatises written by engineers on the feasibility of floating wind farms, tank farms and nuclear power plants, on the one hand, and of cruise centres, theatres, hotels and golf courses, on the other.

Building on Singapore’s reputation in the offshore oil and gas industry, we are well placed to lead the world in this game-changing solution to harvest food and renewable energy from the oceans.

• The writer, a marine engineer who used to be with Keppel Corporation, is the managing director of Emas Consultants, a shipyard planning company.

A version of this article appeared in the print edition of The Straits Times on October 07, 2015, with the headline ‘Vision SG100: Floating cities in the sea’. Online version: https://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/vision-sg100-floating-cities-in-the-sea